“I am not going to lose Vietnam. I am not going to be the president who saw Southeast Asia go the way China went.” Newly inaugurated President Lyndon Johnson, November 24, 1963.

It had to be over 100, with humidity to match, an oven with no turn-off knob upon my return to Bong Son. My butt was chafing, my shrapnel wounds were stinging, and my ingrown toenails were punishing me with a burning sensation, more painful with each step.

And it was about to get worse with an unexpected ass-chewing, shocking since I was naively expecting a welcome back. Good thing I didn’t waste time worrying about someone patting me on my back (where my shrapnel wounds were).

“I don’t know what kind of shit you pulled in An Khe, but I’m still your boss when you’re out here. Did you get the interview?” Lt. Blankenship greeted me upon my return to Bong Son.

“Yes, but my tape recorder was KIA, sir, though I may have saved somebody’s life,” I answered. He countered, “Yeah, yeah, OK, so you didn’t get the story, and you destroyed government property. Is that about right, Swan?” I didn’t answer.

“Alright, get outta here and get back to work and be sure to take care of your wounds,” he snapped sarcastically.*

After I reported on the Ambush, I noticed that Lt. Blankenship was treating me differently and not in a good way. I could not fathom why. Now it was getting worse (like the condensing greeting above). Understandably, my morale was low.

Little did I know that someone would come to my aid during this challenging period. I would find it to be none other than the two-star General who happened to command the 1st Cavalry.

I had the occasion to interact with Maj. Gen. John Norton, not long after, my lieutenant had dressed me down. He was giving his last interview as commanding General with a reporter, where I was present, hosting the newsman.

He remembered me from the field where he presented the Silver Star to Hagemeister the morning after the Ambush (Chapter 17) when I interviewed him. The General seemed sincere when he asked me how everything was going. I stuttered in my response, saying nothing specific. I believed he sensed something was amiss.

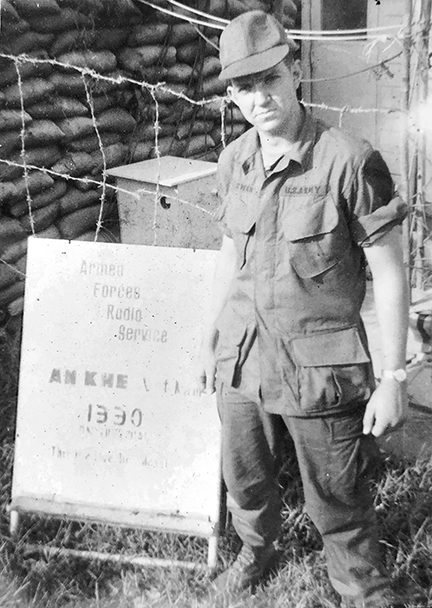

Within a couple of weeks, I was promoted to Spc. 4 and called back to Camp Radcliff with a new assignment. I was to be the Morning DJ on the recently reactivated AFVN in An Khe!

I suspect the General had an aide call Major Witters, head of PIO, and ask to speak with him presently or for an immediate return call. The difference in rank from a major to a major general is considerable. The General probably suggested I get a break from the field.

I thrived at AFVN, An Khe. I dedicated songs to chopper pilots, artillery, engineers, infantry, and men like the ones I had met in the field. The soldiers who were doing the real work.

Of course, men who were in the shit would not be listening to AFVN. But in the field, somehow, the troopers found a way to listen to the hits emanating from An Khe.

There were reports from GIs in the field; their transistor radio was second only to their M-16, and music was like the comfort of a pet. Chopper and other pilots picked up my broadcasts on their FM frequencies.

It was good for morale; songs they had listened to with their wives and sweethearts, like (You’re) My Soul and Inspiration by the Righteous Brothers, When A Man Loves a Woman by Percy Sledge, and Cherish by the Association. But, most importantly, they were reminded of what awaited them back in the “World.”

Occasionally, I got fan mail from women who lived in nearby villages. One, in particular, asked me to play songs for GIs she’d met, I can only surmise, while they were in the village of An Khe, aka Sin City (probably when they were picking up their laundry).

I didn’t dedicate the personal — “From Kim to Larsen and Knelly”— but I did play the songs she requested, doing my part for “Winning the hearts and minds of the people.”

There were no Arbitron ratings in the combat zone. But among the 25,000 or so GIs who had access to my show, it was estimated (tongue in cheek) that I had almost as many listeners as Hanoi Hannah.

About the over-hyped “Good Morning Vietnam” thing made famous in a movie of the same name by the late Robin Williams, most GIs detested the “greeting.” In some rare cases, grunts after hearing “Goooooo-o-o-o-o-od Morning Vietnam” one too many times, promptly shut down their radios courtesy of their M-16s.

Obviously, these men found no “Good” in their morning and didn’t need some smug DJ sitting in the comfort of an air-conditioned studio in Saigon telling them it was.

There was no Good Morning in Vietnam despite the movie that portrayed Vietnam as a place to be romanticized, in my opinion, and a soundtrack that included What A Wonderful World!”

As for our little station in An Khe, my only real friend in Vietnam, John Bagwell (1st Cav PIO), was enthusiastic about our operation and did many things to improve it. He talked Seattle’s KJR rock station into sending us current hit records and some oldies.

And unbelievably, by just writing a few letters, he convinced a popular production company (in the U.S.) to record professional jingles for 1330 AM & FM AFVN, An Khe (valued at $2,000 in 1967 money).

Bagwell was a genuine radio guy who did a lot for our station and made our operations better for the troops we served. Late in his tour, he saved a cameraman’s life while working with an NBC reporter he was hosting near Khe Sanh. Bagwell almost lost a foot in the engagement and nearly became a POW.

Bagwell received the Bronze Star for Valor and Purple Heart.

“John, I will never forget you and the good you did in Vietnam. You never got the credit you deserved for your deeds in An Khe and other efforts.

I hardly made any friends because I traveled so much, but with so few, thank goodness, I had a friend in you.”***

Go figure, on 5 Feb 1968, the only real friend I had In-Country was almost captured and nearly killed. (A priest helped hide him in his church, separate from his weapon.)

But the bad news gets worse, on that February day: Six of his PIO comrades were captured from the Hue AFVN facilities. Steve Stroub, a recent colleague, an An Khe DJ, was executed by the NVA shortly after he was taken prisoner. Two more soldiers were killed during the attack on the AFVN studios. And the remaining five PIO members that were captured at Hue became POWs and spent five years in captivity!

When a fellow vet notices my Cav patch. I’m immediately asked what unit I was with. When I reply 15th Administrative Company. It doesn’t sound nearly as impressive as the 2/7 Seventh Cav. They are apt to think I was a REMF (Rear Echelon Mother F–ker). I ask them to read my book.

I was proud to be recognized for my efforts at PIO and AFVN, An Khe. Here’s a clipping that ran in the 1st Cav’s official newspaper in 1967, The Cavalier.

Incidentally, the same Mike Larson who pinned the above has written Heroes, A Year in Vietnam With the 1st Cavalry Division. Published by and available from iUniverse.

Songs that stand out from my time as a DJ in Vietnam are Happy Together by The Turtles, Strawberry Fields Forever by the Beatles, 96 Tears by and The Mystreians, and naturally, We Gotta Get Out Of This Place by the Animals.

Although I had an easier job now (and no interference from Blankenship), I was anxious to get home to Marty. Unfortunately, I still had a long eight months remaining. I used to pinch myself — yeah, I’m really in Vietnam.

*Unfortunately, some Officers and NCOs in Vietnam were quick to display condescending behavior toward low-ranking GIs like myself. In my experience, they were in the minority.

**I was back in the states when I received a letter from Bagwell, who was still in Vietnam, telling me that my replacement was killed shortly after their move to Khe Sanh (I had missed Khe Sanh and Tet by just a couple of weeks and I would have been in Hue).

***Although I didn’t get to know many of the men — remembering what my 1st Sgt. said about not making too many friends — here are some who were with PIO, An Khe: Maj. Witters, Capt. Coleman and Master Sgt. Bradley. Others whose ranks I don’t remember are Larson, Grizzle, Knelly, Basile, Ferrel, McGrath, and Jim Pruitt. (Not sure of all spelling.) Many members of PIO went on to distinguished careers in journalism, including Donald Graham (before my time with the Information Office), who eventually became publisher of The Washington Post!

I don’t remember where I was on July 27, 1967, even though I would turn twenty in a few days. But many Sailors would remember where they were on that dat, and they would never forget. One hundred and thirty-four gave their lives fighting the fire aboard the USS Forestal (aircraft carrier deployed near the coast of Vietnam). About 167 were horribly burned, with many experiencing a lifetime of pain.

I particularly like this chapter. Probably due to the insight that you gave with your description of your involvement on the front line, the friends you made during this time and, of course, the photos of you in army fatigues. You look in good physical condition and the rations must have agreed with you. In high school you were often the first in the lunchroom and the last to leave.

I imagined that your role in Vietnam was mostly behind the lines and did not involve much risk but I see that was not the case.

LikeLike