The US Army Airfield at An Khe was barely long enough for the huge USAF C-130.* After a hard touchdown on the perforated steel plating runway, it quickly reversed thrust and stood on the brakes to prevent overshooting. I had just arrived with 75 other replacements, closer to the war.

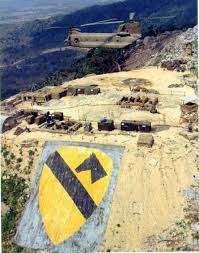

Here in the Central Highlands of South Vietnam was a sight to behold: the elite 1st Cavalry Division (Airmobile), headquarters for “The First Team,” with 16,000 soldiers. That included Airborne, Ranger, Pathfinder, and other specially trained Skytroppers. High-tech gunships and support helicopters numbered 434.

Because of those expensive weapons-of-war-aircraft and other security concerns, Camp Radcliff** (unlike most other large US bases in Vietnam) was off-limits to Vietnamese Nationals. The enemy made up for this prohibition of their fellow Vietnamese by launching mortars our way almost every night.

My temporary quarters would be at Camp Radcliff, near the PIO headquarters building. It was less than a hundred yards from where our helicopters sat on standby, stationed between revetments. From there, they lifted off for combat sorties and (hopefully) returned for fuel, munitions, and maintenance.

While looking for a place to bunk, I thumbed the small wheel on my transistor for better reception while AFVN Saigon played Bend Me, Shape Me by the American Breed.

I found a smelly fold-up cot with mildew stains in an empty corner of an old hooch. Although my shanty was leaky and odorous, I didn’t complain much after sleeping in the elements with no shelter, and usually, the dirt while on field assignments.

It’s damn hot here during the day, and if a mythical VC was stoking the flames, they took the nights off to lob some mortars our way. Because it got chilly in the evening.

I was one hut over from the quarters of a slender USAF major from Ohio, the Weather Officer for the 1st Cav. The nightly booms and echoes we heard were unrelated to a weather event. It was our 105-mm artillery (harassment & interdiction) rounds that filled the night.

We lay half-awake and alert for a different sound — the whistling and Whoosh, Whoomph, Whoomph, and splat of incoming mortars. Although the VC typically aimed for our helicopters, we were close enough. Most of us who occupied makeshift shelters near the choppers had access to a bunker.***

The enemy wouldn’t mind if a couple of GIs were also taken out by the mortars, which they frequently sent our way. As for the GIs at base camp, those rockets likely created the most danger, although slim, for those rear-echelon soldiers who weren’t near the flight-line.

Camp Radcliff was surprisingly orderly, even with several dissimilar shelters. There were tents, hooches, barracks, orderly rooms, dispensaries, chow halls, etc. Sandbags were stacked high around most. Trash was minimal, probably as a guard against damage to aircraft engines.

On my first day moving around camp, the heat was in the high eighties, and it was dusty. I encountered groups of weary line soldiers, most on a short break from the field. Almost everybody was talking about one of our undermanned Cav companies being nearly wiped out by the NVA less than two weeks ago.

Twenty-eight of our soldiers were killed, and 87 were wounded at LZ Bird. In one platoon, the six men who survived were saved by the firing of a beehive round, its first use in Vietnam.

The projectile is a canister containing 8,000 fléchettes (darts) of metal fired horizontally and at ground level from a 105-mm howitzer at 488 meters per second. It obliterates everything in its line of sight. (A description of the battle, written by Spencer Matteson, a man in the thick of it, is included in Book II, Chapter III, Bad Night at LZ Bird.)

In the context of that horrific battle — the dead, the wounded, the overwhelming fear and hopelessness — my first detail at the camp, as a honey-dipper, didn’t seem so bad.

A fifty-five-gallon drum cut in half, two-thirds full of diesel fuel, sat below the holes in the camp’s outhouses. When they were about to overflow with crap, someone needed to burn it. That task would go to low ranking enlisted like me.

Here’s a brief indoctrination, for the layman, on the art of burning shit: Grab the rebar-type handles welded near the top and carefully pull the honeypots from the outhouse. Add diesel, stir a little, throw in a lit match, or carefully lower a Zippo®, stand back, and watch it burn and the black clouds rise.

This burning was done in the heat of the day, and during the monsoons, it was not an ideal spot to dry out. On the upside, when you were burning shit, nobody fu–ed with you.

In a few hours, while stirring (making soup), the turds would be crispy enough to dump. Refill the drums to the proper level, then push them back under the outhouse holes. All done. Unsurprisingly, this was known as the shit-detail — literally.

Given a choice, I’d take it over KP without hesitation; working in the mess hall, peeling spuds, scrubbing pots, and taking shit from a grumpy old mess sergeant was a 10-12-hour detail. I got to do plenty of both.

I could have skipped BCT and AIT and come straight over and given the Army an extra fourteen weeks of those fetid details. Local nationals (who usually did that work) were not allowed on the base camp.

Maybe those shit details (GIs did instead of locals) saved some choppers from a satchel charge, perhaps a soldier, too.

Now that I’ve considered the big picture, I should have been whistling Dixie instead of bitching about this wretched duty. Having performed that unseemly work, you are more aggressive in the jungle. Okay, I just made up that last sentence. But it’s possible.

As for actual work, I hosted news media from the states with briefings, some press releases, and a few other viable tasks at the 1st Cav PIO. One such event included a radio reporter from Chicago whom I was assisting. He had just arrived in Vietnam and wanted to go straight to the 1st Cav, where the action was.

I met him at our PIO in An Khe at 21:00 hundred one evening, just as we were getting some incoming.

He turned on his recorder. In a high-pitched voice, he announced. “I’m. . . in An Khe, South Vietnam [heavy breathing, hyperventilating] and we’re under attack [near screaming] at this moment by the NVA.” He was yelling so loudly and overmodulating (as we call it in the business) that he almost drowned out the whoomp, thump, and splat of the mortars.

(I still have a copy of that recording somewhere in my cluttered cottage. But, naturally, not the more significant ones, like my newsworthy interviews and bits of my radio show.)

His recording reminded me of a radio reporter (also from Chicago) who, thirty years earlier, witnessed the Hindenburg crash in New Jersey. He described it as “The worst catastrophe in the world . . . Oh! the humanity . . . .” Although it was a terrible event that killed 36 people (62 survived). The reporter was widely mocked for his over-the-top narrative.

Although there were no injuries here, and mortars are no joke, I got a good laugh from the An Khe recording. The reporter was a bit embarrassed, too. We were a far cry from being “under attack.”

He and other reporters wanted something more substantial than a routine rocket barrage. They wanted to go where there was fighting.

I, too, wanted that. I didn’t go through BCT, become a highly trained killer, and a Broadcast Specialist for shit details.

Unlike most support personnel, I had the option of volunteering for the forward areas. And that I did.

It would prove to be more interesting and a lot riskier than burning shit. Smoke ’em if you got ’em.

The Private at the Armory in An Khe didn’t question my choice or amount of armament once he found out where I was headed.

I had never seen, let alone fired, the recently introduced M-16 I was issued. Find a way to site it, he said.

The Halzone he gave me was for water purification; the salt tablets were to prevent heat exhaustion. Oh, and don’t forget the primaquine, an anti-malaria pill, once a week, he reminded me. “Better take the damn things and try not to get shot,” the Private said.

Getting shot was just one of the things to worry about. The Black supply sergeant who overheard the private reminded me there are a thousand and one other ways to die over here:

“You can get rocketed, mortared, bombed, bayoneted, step on a land mine, a booby trap, or walk into a punji pit.

Your helicopter can crash, or run into its blades while entering or un-asing.

Your bunker can cave in. You can die from heatstroke or from being napalmed by friendlies.

You can ingest ground glass or battery acid; the VC has been known to put in GIs’ beers and Cokes.

You can die from a rat bite, a dog bite, gored or stomped on, or spiked by a pissed-off water buffalo bitten by any number of poisonous snakes.”

The sergeant looked at us with a half-assed grin and concluded, “Man, war ain’t only hell. It’s a Mother F– ker.“

(From LRRPS In Cambodia by Kregg P.J. Jorgensen, and 1st Cav newspaper The Cavalier, with permission.)

Before I left for “Indian Country” farther north, I was told the 1st Sgt. was looking for me. When I stood before him, he said in a raised voice, “You’re out of uniform, soldier.”

I was looking around my fatigues and jungle boots warily when he said: “Don’t worry, Swan, [he said jokingly] your rank is not displayed. You’re a PFC, have been since you got here.” (Enlisted and officer insignia were not typically displayed in the field.)

“Thanks, 1st Sgt,” I said, “Wish I’d known that last night when I was on the Greenline pulling guard duty.”

What had happened was that the other trooper with me in the guard tower kept ordering me around. Even though we were both privates, he’d reminded me he had been In-Country longer, and I fell for the petty rank-pulling.

As a PFC, I would have said, “No, you’re going to check the Claymores**** this time.

Then, the 1st Shirt wished me luck, told me to keep my head down up there, and not make too many friends.

When I lumbered onto the ramp of the C-7A Caribou at the An Khe Airfield, bumming a ride to Bong Son, I had with me just about all I could handle. So did the Caribou, with room for just one more, me.

Let’s see, M-16 with bayonet and six magazines of ammo with eighteen rounds each instead of 20 (less chance of jamming). Check. Six M26 grenades. Check. M-79 launcher (thump gun) with six 40mm rounds. Check. Mk V .455 (not army-issued) sidearm with lots of rounds. Check.

You get the idea; I also carried beaucoup pills, a gas mask, first aid supplies, razor/toiletries, and an entrenching tool.

Then there was mosquito repellent, a net, a poncho, a liner, and C-Rats with a P-38 can opener. I carried five canteens of water, an extra pair of socks, a pistol belt, and a rucksack to keep it all together.

Finally, there was my 10 x 10-inch Panasonic® RQ-1025 reel-to-reel tape recorder, with an improvised strap, extra batteries, Marty’s letters, and about 50 lbs.

Although the strip at An Khe was long enough for a leisurely takeoff, the pilot “pulled the guts” on the little Caribou. He executed max vertical takeoff, and we were at speed and altitude swiftly.

I had no preconceived notion of whom I would encounter on board. But I wasn’t expecting what I saw: A half-dozen Green Berets with CAR-15s (Modified M-16s), Chopped M-79 Grenade Launchers, and sidearms I didn’t recognize at the time. They weren’t wearing berets. Their headgear was green cravats with uniforms in leaf-pattern camo, sans patches, name tags, or insignia.

Onboard for the short lift to Bong Son, they weren’t engaging in horseplay. They were quiet and looking straight ahead. I thought it unwise to ask, “Wassup?” (Oh, wait, that trash-talking hadn’t been invented yet.) I surmised that saying or asking nothing was wise, and that’s what I did while sitting atop my helmet in the droning Caribou.

Several Marines were also abroad; they had a small detachment in Bong Son. They weren’t completely stoic, but were not loud, laughing, or telling jokes either.

The Caribou we were guests on is a short-takeoff-and-landing (STOL) tactical transport aircraft. It can land with as little as a thousand feet on an unimproved strip.

These twin-engine prop jobs were workhorses that kept US troops moving. It freed up valuable helicopter time for our soldiers who needed to get in real close. Bong Son would be that place.

The pilot touched down in the dirt, reversed thrust, and rolled to a quick stop. The crew chief dropped the already open ramp further to the ground, and we disembarked forthwith — Special Forces, Marines, then me.

15

*In 1967 alone, 35 souls were lost to C-130 crashes at the An Khe airfield.

**Named after the first 1st Cav casualty near the camp, an army major.

***At base camp in An Khe, once the mortar alert was sounded, everyone was required to rush into the bunkers (when available). Some just slept through the warnings, rhetorically asking "what are you going to do, send me to Vietnam?"

**** A curved 3.5 lb Antipersonnel mine that scatters 700 steel balls when activated by wire, directions embossed on the weapon: "This side toward the enemy."